Body of IITR

This question shall haunt you like a stubborn ghost for the initial 3 semesters of study – asked by professors to gauge your understanding of it – so it pays to know.

The standard definition – offered by a number of dictionaries – proclaims architecture to be “the art and science of designing buildings, open spaces and physical structures”; however, to fully appreciate the definition, one needs to understand the keywords better.

Art: As most people reading this would expect, architecture has several aesthetic considerations, “space” being the central one. Space is perhaps a very abstract concept, but it can be understood as the enclosure within which one is positioned. Your bedroom, living room, the dormitories you will come to live in – all – are spaces, although of differing quality. This quality is ascertained by the way the light filters in, the way the wind blows across the room, the sounds and smells that can be heard or smelled within a space, and myriad other factors. An architect’s duty is to make them more liveable and enjoyable to offset the mundanity of everyday life, or to elevate its loftiness.

Science: The science component only slightly resembles the kind you have been exposed to thus far. In architecture, science is a combination of principles and quantitative problems (numericals), with the former predominating. Architecture has several logical considerations, some of which are climate, cost (of construction, of running), making sure the structure/ building does not collapse and actually constructing whatever has been designed. Details shall follow in the next question.

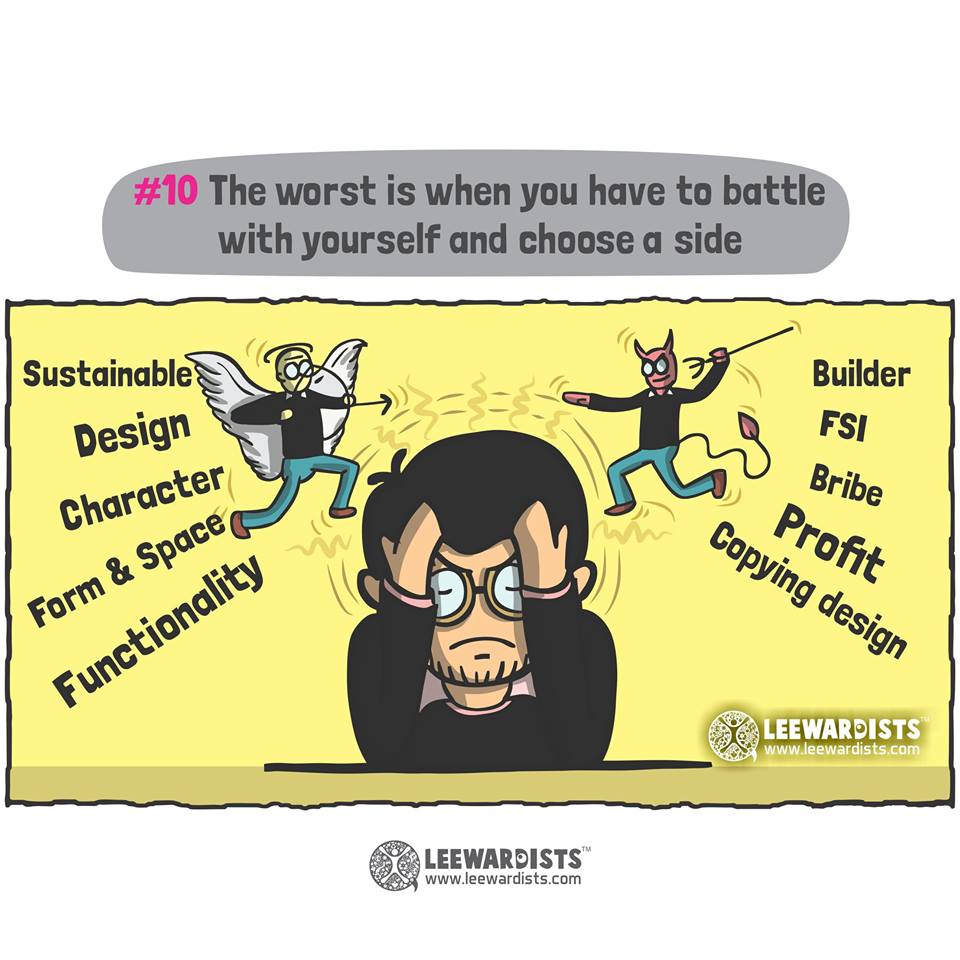

Design: Design consists of juggling aesthetic, practical and several other parallel considerations to arrive at the best possible solution. In the case of architecture, one has to consider the sequence of spaces/rooms (their connectivity with each other), the climate, the cost, the materials that ought to be employed, the aesthetics, etc. and produce a design that pacifies each need. It is best learnt by practice.

The study of architecture requires one to be a generalist rather than a specialist. The constituent courses of the bachelor degree, as ascribed by the Council of Architecture, are centred around “Architectural Design”, which will be found in all semesters except the first (1.1) and the last three (4.2, 5.1, 5.2). In the fifth year, one works on their Thesis, a culmination of all skills acquired during the last four years, where he/she designs a building from start to finish, just as one would for an actual project. Other courses impart necessary skills and information required in order to design and actually construct a building. These include climatology, structures, building construction, architectural graphics, visual art, building codes and regulations, etc. A full list of courses – and details about them – can be found here

Each year has its own studio, a large room where they do most of their drafting; it comes equipped with an anthropometrically sound furniture set comprising a drafting table and a stool. A standard set of equipment comprises a parallel bar (a 100-something cm long scale that draws parallel lines), an adjustable set square, a sheet holder, A1, A2 or A3 sized cartridge sheets, a great number of pencils, an eraser, a cutter (to sharpen pencils with; sharpeners are for amateurs), and a fine-liner, although only the first and third are exposed.

To evaluate designs, a jury is conducted, where professors – and sometimes peers – criticize each design while the designer attempts to justify his decisions. Juries may severely damage egos or ignorance, depending on how one takes the criticism. Nevertheless, juries are the primary means of progress for any architectural design course.

Contrary to popular belief, architecture is not all about drawing, painting, and the like; although these are helpful skills during the course, they play a very preliminary role in design, and can nevertheless be picked up after joining the course. One does not need to be creative in the visual sense to take up architecture as a profession.

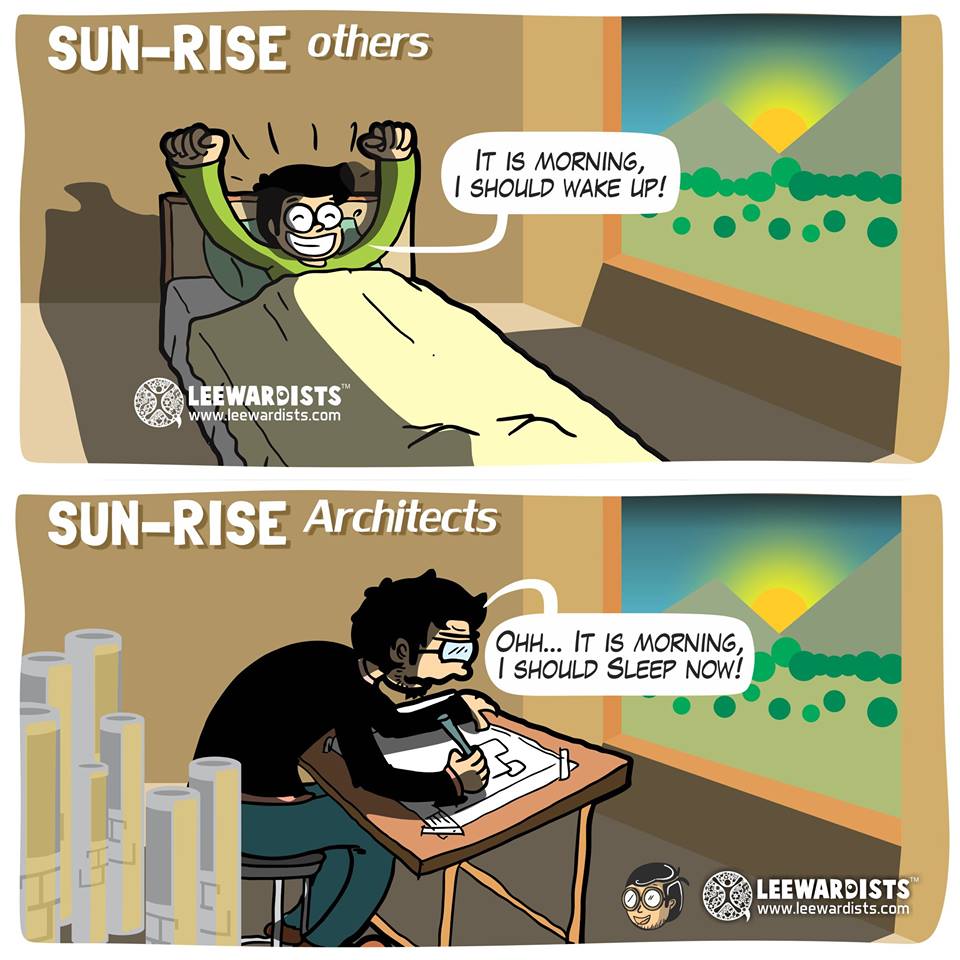

The course as a whole is rather challenging. It involves the longest contact hours of all courses and a great load of assignments, both of which – thankfully – eventually decrease. Good grades call for a mastery of all courses and fields – most importantly architectural design, which has the highest number of credits in any given semester. Architecture involves solving the biggest problems as well as the most minute. All these manifest as a great degree of frustration and a considerable number of late nights. For people who have studied the sciences all their lives – presumably with much interest and love – this will be a very different ball game.

If architecture is what you are interested in, IITR is perhaps not the best place to pursue it. A list of reasons are given below:

Lack of competition: Out of the thirty-something classmates that will constitute your class (most colleges have at least 70), very few will actually be interested in architecture. A great number of them shall turn in a very poor quality of assignments – if they do – aiming at just keeping their heads above the water. There is a tendency for the “good students” to become too self-sure and swim in seas of mediocrity.

Focus of the professors: Unlike other colleges of architecture, the primary focus of professors in IITR is their body of research. All professors are highly qualified (holding at least a M. Arch degree; most have a PhD), although in their specific fields of interest. Only a handful of professors actually put in effort to keep the class interesting and impart relevant and sufficient knowledge. At present, there are only two visiting professors (practicing architects), who are infrequent with their visits. At top architectural schools such as SPA Delhi, this ratio is almost reversed; the design studio and juries are held and evaluated by practicing architects, who have an idea of the real world, of what really works and what doesn’t.

Not enough emphasis on design : Architectural design, as stated earlier, is central to the entire curriculum. However, there are only 9 hours allotted to it per week, far less than any other good architectural school in the country. Design is a reiterative process, and requires constant feedback and work to be done right; 9 hours a week hardly ensures that.

Lack of studio culture: “Studio culture” is an important part of the architecture degree (to know more, watch this ). All schools (almost without exception, including our sister IIT Kharagpur) leave their studios open during the night in order for the students to work on their assignments. It keeps one away from all the distractions of the hostel and ensures that those willing to work get a conducive environment to do it in. However, IITR chooses to be different in this rather inconvenient way.

Skewed sex-ratio: The sex-ratio varies across all years, depending on the collective luck of the incoming freshmen. However, it is much lower than other colleges, where the sex ratio is 1:1 or better (with girls predominating).

You have now managed to read past all the faults and misdeeds of architecture, so pat yourself on the back for a bit.

Architecture at IITR has many unique advantages. These are:

A chance to make another field/skill your profession: Even if one discovers that architecture isn’t their cup of tea, there are many alternate options available, unlike any other college of architecture. Related fields such as product design, graphic design and industrial design exist. Fields bearing little resemblance to architecture include coding, finance, consultancy and start-ups, to name a few. Self-interest and effort are primary requirements in such an undertaking, but campus groups and seniors help greatly. One can build his CV by interning in capacities closely related to the profession he/she wishes to pursue. Interns are much easier to come by with the help of the IIT tag. This is a good point in time to reiterate that very few people in any given batch choose architecture as their profession; the rest go into non-core jobs.

The “Family system” : All first years are inducted into one or more families within the initial two weeks of joining IITR. A family may choose to adopt you based on any number of criteria, or even at random (by chit-picking). Once in the family, the very first responsibility is helping the fifth year with their thesis; here one picks up preliminary model-making skills, and even software skills, should their baap allow it. This duty is renewed every year, but its formal nature is not. In return, it is any baap’s duty to give chaapos and advice on how to weather the storm that is architecture.

Societies, groups and sports: Although architecture constitutes a very small number of the total intake, archi wale log can be found in most groups on campus. The reasons behind joining societies and groups stand as two polar opposites: some see them as opportunities to counter frustration, while others see them as opportunities to learn relevant skills, having discovered their disinterest in architecture. Either way, the number of groups and societies on campus is astronomical, with new ones cropping up every year. Chances are there is a group for each interest or intrigue you possess (an exhaustive list with brief information can be found here ). Similarly, facilities for all major sports can be found here, with exceptional coaching staff that bring out the best in you. The standard of sports are much higher than one would expect for a sorry bunch of nerds. More information can be found here

Semester Exchange : A semester exchange is available for students having a decent CGPA (>7.5); up to three students can be accepted as exchange students in Hochschule Luzern (Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts), Switzerland, in their 7th semester (4.1). This is an opportunity to learn how our western counterparts perceive and approach architecture, as well as to travel Europe, experiencing all that it has to offer. Here is an account of the experience, as recalled by a senior who visited Hochschule Luzern this year: exchange diary switzerland

Research opportunities : Perhaps one characteristic that sets IITR apart from all other colleges is the emphasis it lays on research. Any student interested in research may approach a professor, consult him/her about the area/matter he wishes to investigate – and once he/she has the blessing of the professor – pursue it. In addition to the above, a program called SURA (Summer Undergraduate Research Awards) is also in place. Here, however, the approval is given by the central administration (Dean, SRIC) following a detailed presentation explaining the area of study and specifying the deliverables each week. A student who is shown the green light stays back during the summer, and submits a report at the end, after which he is given a partial refund and a stipend. For students of architecture, an additional opportunity lies in the form of the CBRI (Central Building Research Institute), which, although an autonomous body, abuts our campus. The CBRI develops new materials and ways of building and assists with problems of planning, designing and disaster mitigation. The CBRI is very welcoming of IITR students wishing to research such areas; two seniors (to the author’s knowledge) have written research papers under the CBRI.

On-campus placements : Reportedly (that is, with questionable certainty), other architectural colleges do not have placements, or any sort of arrangements wherein graduates can find firms to employ them. At IITR, such a system does exist, but the number of firms and companies that recruit architects are just sufficient. However, when it comes to other fields such as the ones mentioned earlier, it is a level playing field, and architecture graduates can get non-core jobs provided they are meritorious. More information can be found here

If, after carefully considering all the above information, you still want to pursue architecture at IITR, here are a few pointers that might help you.

Give architecture a fair chance. A considerable number do, but their effort does not sustain, and their enthusiasm dampens within the first two months. Giving architecture a chance entails doing all assignments conscientiously, at least for the first semester (which, in itself, forms an image of architecture that is far from reality).

Read. Whether its articles on archdaily, or books on architecture, the more information you accumulate, the better. Some of the knowledge thus collected will be employed in your designs at one point or another.

Work on improving your visual communication skills , i.e. drafting and sketching. A good (technical) drawing or sketch is worth a thousand words. Competitions organised by NASA (National Association of Students of Architecture) are the best way to do this.

Learn to take criticism objectively. Any professor criticising you or your design is only doing so for your benefit, not to make himself/ herself feel big.

Perseverance is key. There will be classmates better than you at sketching and artistic pursuits, but the belief that hard work can at least equal talent needs to be cultivated and acted upon. Similarly, a lot of your initial work and ideas may be shot down in the jury. Push yourself to do better. Sadly, results are what finally matter, the effort that one puts in merely accounts for consolation.

In case you have any doubts regarding the course that you wish to get clarified, feel free to call any of the people listed below:

Divyang Purrkayastha (2nd year): +91 9560588732

Ramachandra Reddy (3rd year): +91 9557902784

Lanka Adarsh (3rd year): +91 9410577752/ +91 8218618294

Anshul Rathore (4th year): +91 9917026076

Deovrat Dwivedi (5th year): +91 7895473473

Kshitij Joshi (5th year): +91 7895475628

Illustration Credits: Leewardists