Body of IITR

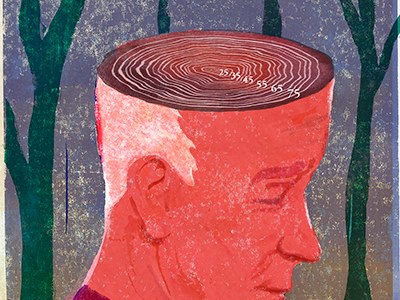

The value of any commodity in our possession – philosophically or economically – is ascertained by a lack of abundance. Life is universal, but never in perfect competition; the longevity and quality of, as well as the insignificant infinite incidents constituting our lives vary globally. Nevertheless, death is the indiscriminate adjudicator that unites us. Perhaps it is the only reason we ever do anything; a visible eventual end reinforces the value of our life, spurring us on to make the most of each day.

What, then, will we – our attitudes, outlooks and dispositions – make of a significant increase in the average life expectancy?

If the (hypothetical) elixir were to bequeath to us an additional 120 years – that is to say, a life expectancy of 200 years – one immediately assumes that scientific and technological progress will accelerate by an unimaginable magnitude, for greater work logically follows greater amount of available time. In retrospect, however, it is short-sighted to exclude the talent for procrastination with which we are naturally endowed. The perception of time as an infinite commodity shall incentivize a majority of the human race to recursively postpone autonomous tasks, resulting in collective underachievement.

Counterintuitively, there shall also be a – eventual, if not immediate – decrease in population. Assuming that most countries of the world shall be developed by the time such an elixir is made available, the prevalent family size shall be significantly smaller. Men and women shall hop in and out of relationships – having enough time to find the “love of their lives” – a hunt that shall, perhaps, forever elude and disappoint them.

Meaning is innate in language but never in life, forged by its bearers (in an attempt) to make sense of the series of circumstances that establish themselves as parts of their lives. It is sought from a definite number of sources – primarily suffering, love and work. Love and work become largely irrelevant in this scenario; very rarely shall these be the sources of fulfilment, and fodder for discerning meaning. By exclusion, we shall turn to suffering to define our lives. What a sad life this shall constitute! With suffering predominating the emotional landscape – and additionally milking it for meaning – an aversion to happiness shall prevail, for it (logically) becomes the antithesis of meaning’s forge.

Wrought and marred by misery, humanity’s faith in the absurd shall be solidified; once the “uselessness of suffering” is established – those that rely on it as the foundation of meaning shall eventually realise that there is none – any reflective, contemplative being shall surrender himself to the reasoning that his/her existence is worth nothing, that nothing will possibly be different on their passing. Employing Adrian’s logic (from The Sense of an Ending) that one may choose to renounce their life upon examination – since it is a gift given to them and therefore, theirs to reject – intellectually endowed people shall renounce their lives the way Adrian did. Who, then, shall lead this world into the great unknown that is the future?

Our lives, although flawed, shall never be as disastrous. Perhaps it is conducive – even ominous – to have a life of eighty years. A supernumerary life may arouse gratitude initially, when one has a standard to compare it to; over time, however, it shall be the source of a universally prevalent disdain.

Illustration Credits: Scott Laumann